The Unreliable Narrator

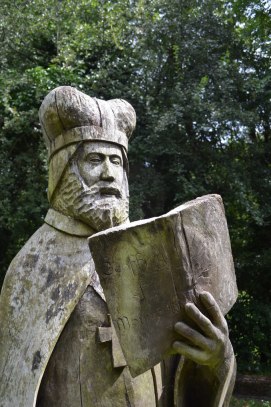

Geoffery of Monmouth (c.1095 to c.1154) was a medieval cleric and historical chronicler of some considerable importance.

His Magnum Opus, “Historia Regum Britanniae” – (History of the Kings of Britain), originally called De Gestis Britonum (On the Deeds of Britons) was a hugely popular book in its day and had a profound influence in the European understanding of English and Welsh history and myth for centuries.

It was critical in creating the Arthurian legends, was used as the basis for many histories of England and Wales and a number of the plays Shakespeare wrote are based upon it (via some intermediaries).

The blurb on one recent scholarly volume on him has it that Geoffrey was “arguably the most influential secular writer of medieval Britain”, and this doesn’t seem to be wildly disputed. (A companion to Geoffrey of Monmouth)

So, a significant figure indeed. And yet it is also true that it a long established tradition to start any discussion on him by referring him by pointing at him and chanting “liar, liar pants on fire” or giving him the moniker “Dishonest, fibbing, unscrupulous, massive manuscript maker-upper, Geoffrey of Monmouth.

And by long established I mean for 850 years or so – pretty much from the time Geoffrey was setting quill to vellum.

Podcast episodes featuring Geoffrey

Now Geoffrey, (or Galfridus Monemutensis in the Latin in which he wrote), is obviously not a folklorist in the traditional sense (for a discussion of who I’m including see: GRAEME YOU NEED TO LINK THE ESSAY IN)

But Geoffrey was was certainly involved in gathering a great many historical stories and legends from a variety of stories. His retelling, or possibly creation, of those legends has gone on to influence a load of the stories that have been told after his time: both through literary tradition but so wide spread were his stories that his tales of the Kings of Britain have been transmitted via oral folklore in the nearly 900 years since his death.

Biography

To start with a brief biographical sketch.

Brief not merely for the sake of brevity but because of the man himself we know fairly little. In fact while this is a summary of my understanding of current scholarship we know almost nothing about him with total certainty.

It feels like it should be safe ground to state that he was from Monmouth, but that’s not quite the case, however opinion does seem to be that he was born on the border lands of Wales, and have some connection to Monmouth which today is a small town in the Welsh county of Monmouthshire, but which in Geoffrey’s time was a more significant place, indications of which can be seen today in the ruins of Monmouth Castle.

Debate also exists about whether he was “ethnically” Welsh. He had knowledge about the area, a name strongly connected to it and his primary work was concerned with the history of the people who were by his time the Welsh.

However stacked against this is lack of direct evidence for a connection with Wales, his name being uncommon there, and also that while he spoke highly of the historic Britons he was not particularly praiseworthy about their Welsh descendants of his time. England and the Welsh borders, were at this time governed by a Norman French ruling class, who remained ethnically distinct, even when born in England.

It’s been suggested that Geoffrey could have been a member of this Norman class, and more particularly he is thought to have been most likely of Breton descent. Breton rulers were common in Wales and the historical tie of Brittany to the Britons could explain his interest in their history. So this stands as a reasonable explanation, but could just as well be wrong.

There is a very good chance that Geoffery might just have been Welsh, and certainly he was widely believe to have been so in the centuries after he wrote, and adopted as a welsh figure by many Welsh writers and historians. Debate continues but seems unlikely to ever be completely resolved.

It seems on firmer footing to claim that Geoffrey spent much of his life in England – and particularly around Oxford, where he was a canon of “The College of St. George” and his name is mentioned in charters.

Canon in this sense is a role within the church similar to a priest or a monk, but taking no vows, and there were many such “secular-canons” at the time. Geoffrey was also known as a Magister – a teacher of some importance who had themselves received higher education.

In the last few years or life he rose further in the church – and became a fully fledged priest and very rapidly thereafter, that is 10 days after, he became a bishop. While this sounds a little dodgy, this rapid transition was not as unusual then as it was today, and from what I could tell was essentially a box ticking exercise to make well regarded secular churchmen bishops.

All in all it appears as though he was a figure of some importance in the Church. Not at the highest echelons but a successful senior management type certainly.

Between 1130 and 1150 he wrote three historical books all in Latin – Prophetiae Merlini, Vita Merlini and the Historia Historia Regum Britanniae. He dedicated the latter to Robert, Earl of Gloucester, a very influential figure during a time of civil war in England known as the Anarchy, and the others to the Bishops of Lincoln at the time. Exactly where his writings fit into his church work I’m not clear, but both were clearly important parts of his life and interconnected, with Alexander Bishop of Lincoln having suggested to Geoffery he write the Prophetiae.

Geoffrey seems to have died in either 1154 or 1155, at the age of around 60.

While there are more bits and pieces known about the man’s life he isn’t remembered some 900 or so years later for the deeds that he did, but for the few books that he wrote.

Prophetiae Merlini and the Vita Merlini

To start with his two lesser known and shoter workers: These two were written roughly fifteen to twenty apart – the Prophetiae Merlini (Prophecies of Merlin) in c.1130-35 and the Vita Merlini (Life of Merlin) in c. 1150.

Both are to some extent expansions on the information on Merlin that is also incorporated in the History of the Kings of Britain. The prophecies list some, well prophecies, attributed to Merlin with a little background. These prophecies are things that by and large have already come true, rather than looks into the future.

The Vita is a poem that gives an account of Merlin’s life, or at least the end of his life, relating his madness, his life as a hermit in the woods, more of his prophecies and his relationship with other figures of Welsh legend – in particularly Taliesin.

Obviously in these works, but also in the History of the Kings of Britain Merlin is a key character that Geoffrey really likes to write about. More than that though, Geoffrey essentially created the character of Merlin across these texts.

There were earlier figures from Welsh legend/history that Geoffrey drew upon: Ambrosius Aurelianus and above all Myrddin, and possibly others Geoffrey claims refers to who we don’t know about, however Merlin as a whole is very much Geoffrey’s creation incorporating bits of these legends and other new bits.

Oddly enough despite him being Geoffrey’s the character and life of Merlin across the three is actually quite different and in no version is this Merlin the tutor to Arthur as he later becomes – he’s much more involved with Uther, Arthur’s Dad, and with Arthur’s birth.

Nevertheless it is Geoffrey’s Merlin figure that makes its way into Arthurian Legend and eventually gives us the Merlin that has become such a renowned figure to this day.

These two works about Merlin were certainly known about and circulated, however they are considerably lesser works when compared to the work for which Geoffrey is really renowned, and why we talk about him to this day: Historia Regum Britanniae.

Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain)

Summary of the book

By far the most important of Geoffrey’s work this book chronicles the history of the island of the Britons for two millennia. The Britons here are the original pre-Roman inhabitants of Britain – understood to have been forced into Wales by the coming of the Anglo-Saxons by the books end.

The original title of the work was De gestis Britonum (On the Deeds of Britons) which probably better reflects its focus. This was the name used by Geoffrey but later copies used the Historia name and it is that which stuck.

The work is in chronological order and starts with “Britain, the best of Islands”, being populated by Brutus (not that Brutus) as related on the podcast and ending in the seventh century.

Written in Latin it is a lengthy read, detailing the rise and fall of many dynasties and, forming the bulk of the work, the battles, plotting, marriages, affairs, murders and intrigue that accompanied their rise and fall. A particularly literate gossip column approach to the plotting of history.

It first covers a lot of “British” kings, British being those supposedly descended from Brutus, with notable characters including.

“Britain, the best of islands, is situated in the Western Ocean, between France and Ireland“

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Opening to “The History of the Kings of Britain”

- King Llud: Who London was renamed after, having originally been called “New Troy”

- King Leir: him of generally being an unreasonable dick to his daughters fame

- King Bladud: necromancer and fatally unsuccessful aeronautical engineer

- Belinus and Brennius, brothers with an on again/off again relationship who eventually conquer Rome

- Blegabred: whose musical abilities were so good he was known as the disco king. Or something like that. My translation might be faulty.

Following this history the events of the Roman attack on Briton the eventual conquest and the centuries long occupation is covered.

After Rome leave the text plunges into what we’d recognise as the world of Arthurian legend – with Merlin playing a key role in events. There’s far more detail to this bit of the text considering the number of years covered. Arthur’s father – Uther Pendragon takes the stage for a bit with a fair amount of detail, and then Arthur’s own life is covered.

This is a far more geopolitically focused telling of King Arthur’s story than later became popular. Though it still has magic and dragons and Excalibur it certainly can’t be described as a romance.

Arthur here is a King who defeats the Anglo-saxons who have taken Britain, conquers or allies with much of Europe and is on the verge of becoming the Roman Emperor when he is forced back to the final battle of Camlann, in which he is kind of killed.

The book winds up telling of the reconquest of the Island by the Anglo-saxons, with the Britons banished to the woods of Wales. And thus begins the real history of Anglo-Saxon England, and the effective end of the history of the Britons.

Sources – the “ancient book”

So. Certainly not what would be considered an accurate history by today’s exacting standards of proof. Which was probably fairly evident from the magic, the giants and the dragons etc… But that’s standard for the time right?

And lots of the Kings Geoffrey mentions do appear to have a very slight historical basis for them. At the very least they do appear to correspond to the names of British kings or more often tribal leaders who existed, at some point or another. However the biographies biographies themselves are far less verifiable.

So it’s not pure fiction – there is quite a lot of truth in there. The latest research suggests it was based on a wide range of sources – from works we still have today by writer such as Bede, Gildas and Nennius to oral histories and genealogies. Geoffrey was a well read man, drawing on Welsh stories, oral folktales, lots of classical texts as well as on the work of other historians of his time and earlier.

But the work is supposedly reliant on one source in particular. This source, as cited by Geoffrey himself is: an ancient “book written in the British tongue, which Walter, archdeacon of Oxford [gave to me]…. and which being a true history …. I have thus taken care to translate.”

It’s from this book and this book alone which we are given to assume Geoffrey sourced all the information that was missing in other histories that existed at the time. This was why his information was better than Bead and Gildas who he particularly calls out as missing this information. And this information forms the bulk of his work.

Geoffrey is very explicitly about the importance of this book. In one paragraph, as quoted below he basically uses this book as a get out of jail card to anyone who might claim he is wrong. Basically “I’ve got the book, you haven’t therefore I’m right, so don’t question it.

“But I advise them [Other Historians] to be silent concerning the kings of the Britons, since they have not that book written in the British tongue, which Walter, archdeacon of Oxford, brought out of Brittany

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Closing to “The History of the Kings of Britain”

And the problem with this is that there is some serious scepticism that this book he refers to exists at all. By which I mean it almost 100% didn’t. Depending on how generous you’re feeling it seems to be a rhetorical flourish or an out right falsification in order to give his work more credibility.

Given his authority to much of the history he has written rests solely upon that book then it looks very simply like he is just lying, about the book’s existence and much else besides.

Furthermore where there are sources that can be identified historians have found examples where Geoffrey seems to have changed them. On other occasions he’s made reference to works by earlier historians, which do not actually appear in the works of those historians.

Which all seems pretty damning evidence.

All in all it seems like while he had real sources for much of his work he also just made a whole great bunch of his writings up, or altered his sources at his leisure, hanging detailed outlandish tales on the bare bones of earlier works.

Reception

Despite this, or more likely because of it, the History of the Kings of Britain was from the off a very widely read text. For a given value of widely relative to time of course – by which, I mean restricted to the very tiny numbers of the literate upper classes!

But still for the time, and for centuries after, it was one of the most popular works, reproduced over and over again, not just in England and Wales but right across a Europe that shared Latin as a language of scholarship, with many reproductions of the work made. There are over 250 manuscript versions available to this day, and I’m given to understand that was a lot.

It was accepted as real British history by a good number of its readers and so the legacy of the book was huge – For one: it was incorporated into histories for centuries to come, appearing in the works of many historians.

This included appearing in Holinshead’s Chronicles in the 1500s, a work from which Shakespeare was to use heavily when writing is historical plays – which are therefore ultimately based in Geoffrey’s work

It was also instrumental in creating the Arthurian romances that were to become international sensations in the centuries after Geoffrey lived. While these expanded significantly on his text it was the Historia, transmitted via writers such as the Norman chronicler Wace, that was the spark which lit the great fire of Arthurian Romance – surely the most famous and widespread of all legends of England and Wales.

It is true to say that the whole canon of British legends would look radically different without Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Criticism

But dating almost from its genesis Geoffrey’s work came in for some serious criticism from sceptical scholars searching for true history, in spite of Geoffrey’s “I have an ancient book” defence.

William of Newburgh and Gerald of Wales, who wrote a generation or so after Geoffrey threw some serious shade on his work. And this despite the fact that they are both chroniclers who might yet appear on the podcast for their own quite fantastical accounts!

Pulling absolutely no punches William says flat out that “no one but a person ignorant of ancient history, when he meets with that book which he calls the History of the Britons, can for a moment doubt how impertinently and impudently he falsifies in every respect.”

He reserves particular annoyance at the presentation of the Arthurian legends as real history. “it is plain that whatever this man published of Arthur and of Merlin are mendacious fictions, invented to gratify the curiosity of the undiscerning.”

”A writer in our times has started up and invented the most ridiculous fictions concerning them [The Britons]”

William of Newburgh giving Geoffrey both barrels

Do tell us what you really think William.

Gerald of Wales is less straightforward in his criticism but just as strong. He tells a strange lengthy parable about a man who can detect lies using devils that assist him. Which is pretty odd on its own.

But the whole thing is basically just a set up to describe how those devils go crazy whenever the History of the Kings of Britain is placed anywhere near the guy.

This idea of Geoffrey as a dishonest fantasist has continued to the present day, though it’s not quite as straightforward as this idea having universal acceptance.

Academic arguments still rage (or gently simmer) over the sources Geoffrey did have access to and over exactly how much he invented and to what degree he differed in this from his contemporaries and even over whether his writings were actually an elaborate parody of other history writers at the time – though if this latter was true it was clearly quickly forgotten given the books widespread success and repetition as genuine history.

Summary

While there is certainly a lot of nuance to be sorted out it still does hold as a generalisation to say that in his joining together of his various sources Geoffrey made a whole load of stuff up.

And it also holds to say that despite this, or more precisely because of it, The History of the Kings of Britain remains to this day an entertaining read and a source of all kinds of excellent and bizarre stories.

What is a loss to the serious historian is a significant boon to the story teller.

This is most obvious in the stories of King Arthur and the works of Shakespeare, where the lating impact of this work is profound, but it also applies to all the many lesser stories, such as those told on the podcast.

I personally loving reading Geoffrey and seeing another new oddity I’ve not spotted before, or creating new interpretations on his many odd tales.

It’s also good to have some small, blurred window into legends and folk tales that existed some 900 years or so ago. However inaccurate the view might be without Geoffery it’s very possible we would have lost those entirely.

So for the sure entertainment value of the works I’m definitely a Geoffrey fan, and I hope in time that more from his work makes its way onto the podcast.

Episode pages featuring Geoffrey

Selected Sources

- A companion to Geoffrey of Monmouth – a comprehensive work. If you want more on Geoffrey here is where to get it

- The Reputation of Geoffrey of Monmouth – Professor Siân Echard

- Lost voices of Celtic Britain – Dr Miles Russell

Works by Monmouth

- History of the Kings of Britain

- The Vita Merlini

- Welsh Manuscript Version – not so much to read, but lovely to look at

[…] writers combining British (that is Welsh and Breton) legends and settings, such as those written by Geoffrey of Monmouth, with those of continental works – paving the way for Vulgate Cycle. This is why he may have […]